Inside the IRA: Bobby Storey’s Story

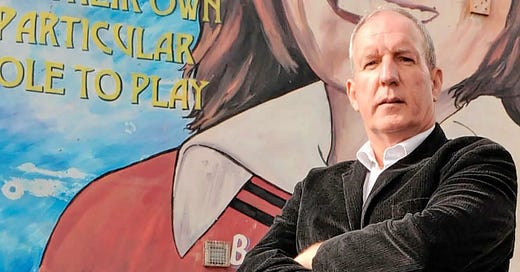

Hailed as the most successful Republican spymaster since Michael Collins, the late Bobby was a reluctant interviewee. But during two in-depth interviews, I got a good insight into what made him tick.

The tension on the streets of Belfast was palpable. The wailing sirens of the army bomb disposal unit could be heard making their way to the latest bomb scare at a shopping centre on Crumlin Road.

Sadly, such incidents were once again all too commonplace in the North when I visited there in 2010 for my second meeting with the infamous Bobby Storey, who was once described in the House of Commons as the IRA’s director of intelligence.

Storey was labelled ‘The Enforcer’ for ensuring the ceasefire held during the peace process talks. As Sinn Féin Belfast chairman, it had fallen on his broad shoulders to persuade dissident Republicans too to choose the ballot box instead of the Armalite.

As far as I am aware, Bobby Storey only ever conducted two in-depth interviews - both of them with me for Hot Press magazine and the Irish Daily Mail. It had taken many months to secure the first interview, which lasted over 90 minutes, but it only took one phone call to set up my second interview with him when he’d seen the first six-page piece was fair and balanced and did not misquote him.

Security at the Sinn Féin office on the historic Falls Road was tight. After a brief once-over by the security men, I was ushered up the stairs – where I bumped into Gerry Adams who stopped to say hello and asked me how my daughter was doing and if I was still, at that time, living in Mullingar. I was surprised that Adams, whom I had interviewed at least four times, had remembered so much about me.

After this brief chat, I was brought into a small upstairs office. Storey, then 54, was sitting at a table, with a bank of CCTV monitor screens behind him. [He passed away at the age of 64 in June 2020.]

‘I don’t normally do interviews,’ said Storey, who had agreed to meet me at the time because he felt it was important that Sinn Féin got its point across about these dissident groups.

As he rose from his chair and offered me a warm and firm handshake, I found it hard to believe that this affable and quiet-spoken giant, who towers over me at six foot and four inches, was allegedly once one of the IRA’s most infamous killers.

American historian J. Bowyer Bell, the author of the definitive account of the IRA, The Secret Army, claimed that Storey was a gunman ‘good at his trade, without mercy, compunction, or moderation’ and that he ‘killed on order’.

It was a description that Storey rejected out of hand. It was certainly hard to reconcile this image with the man who was sitting across the table offering me a cup of tea.

But Storey still had a tough guy image on the mean streets of Belfast. When rioters – with supposed dissident connections – caused havoc in Ardoyne during the summer of 2010, it was Storey who was sent into the middle of this battlefield to quell the situation. He even went as far as confronting looters and taking two stolen cash registers from them, before handing them over to the police.

However, this persona was only one facet of the deeply complex man dubbed the most successful Republican spymaster since Michael Collins.

It was reputation no doubt cemented by the allegations that this man, whom the police nicknamed Brain Surgeon, was behind the robbery of highly sensitive computer files and documents at the Belfast headquarters of the police service in Castlereagh back in 2002.

The sensitive documents included the names and addresses of all of the North’s Special Branch officers, their informers, and prison officers, and cost the British government more than £20 million to readdress the situation by re-housing all their people on the list.

It was also alleged that he was behind the £26.5 million Northern Bank Raid in 2004, described as one of the biggest bank robberies in history.

But Bobby went to his grave without admitting to playing any role in the operation. ‘The only time I was in Castlereagh was on those occasions when I was arrested. And on some of those occasions brutally tortured,’ he told me.

‘Those are the only memories I have of Castlereagh. I know absolutely nothing about the Northern Bank Raid. The IRA said that they had no involvement in it, which is good enough for me.’

When the RUC attempted to bring Storey in for questioning over the Castlereagh raid, it reportedly took them over 40 minutes to get into his house, which had reinforced steel doors and bulletproof windows. Apparently, Storey nonchalantly got up and made himself breakfast while the RUC tried to gain entry.

‘Did you ever see the film Leon?’ he asked.

When I nodded my head, he explained that a scene from the film, in which dozens of heavily armed riot police stormed up the stairs to capture a hitman, ‘was exactly like’ his arrest.

Even though he escaped a prison sentence on that occasion, Storey spent more than 20 years in jail, with his final release in 1998. He refused to talk about his personal life but I understood he was a devoted family man who cherished his partner Teresa – whom he only met after his release from jail – and their three boys, all grown up. ‘My first concern is for my family, their safety and their contentment,’ was all he would say on this subject.

He has been accused of a litany of terrorist acts, such as murder, kidnapping and bombings – including a bomb attack on the Skyway’s Hotel in Belfast which he was arrested for in 1976. But Storey was never convicted of anything more serious than having a firearm following a gun battle in which a British soldier died – resulting in a lengthy 18-year sentence.

Growing up in North Belfast as one of four children, Storey said he was inspired by two events to get involved in the Republican movement; the first was his family being ‘put out’ of their home on two occasions by loyalist gangs; while the second was the bombing of McGuirk’s Bar, in which 15 Catholics were killed.

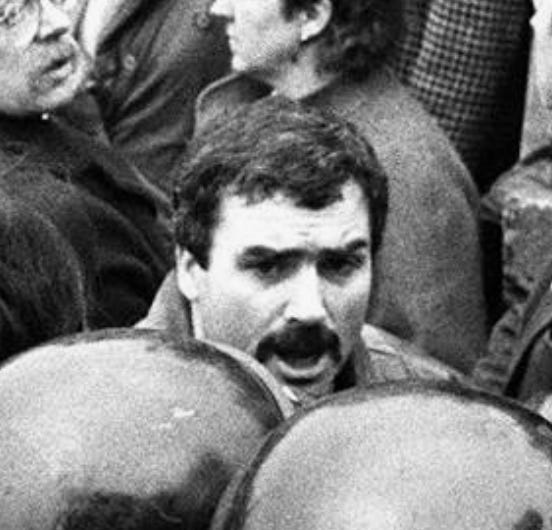

‘I know that had a substantial impact on me because some of the people were friends and neighbours. And, of course, the massacre in Derry – Bloody Sunday – had a massive influence on me. There didn’t appear to be any route or method of response or resistance except to become a Republican activist. There wasn’t really a strong Republican background ethos in our family, other than we voted Republican... What happened was – because of the pogroms my father got involved in the local defence committee and my brother joined the IRA. He ended up in jail in 1971.’

So how did he respond, in concrete terms? ‘There didn’t appear to be any other route or method of response or resistance other than to become a Republican activist. My father got involved in the local defence committee and my brother joined the IRA. He ended up in jail in 1971. I became a Republican activist in the summer of ’72. Harassment of youths my age was very common. The RUC and British army would have stopped, harassed and arrested people on a daily basis,’ he explained.

‘In my own case, I was arrested over 20 times in a four-month period. They tied me up once and threw me out on the Shankill Road; they beat me up at a chapel one night. My experience was no different from many other people’s experiences. These were the things that brought me to be a Republican activist.’

I was struck by how he used the word ‘pogroms’, which is a normally associated with violence against Jews. Was he really comparing the suffering of Catholics in Northern Ireland in some ways to that of Jews in Europe during the Second World War?

‘It was that bad because there was institutionalised sectarianism within the State. It wasn’t just Unionist or Loyalists mobs which were burning down areas of Nationalists in west or north Belfast – the crowds were either being accompanied or lead by the B Specials. If they weren’t being lead by them on occasions then they were standing by and watching.’

Growing up, he must have hated Loyalists? ‘Hatred has never been a part of my outlook or perspective. I’ve never really hated anybody. I’m not driven by hatred or negative forces – I’m more motivated by what I can do about something. I’ve no sectarianism in me.’

But wasn’t the conflict in Northern Ireland fuelled by a religious divide? He answered, ‘I’m not particularly motivated by religion. I don’t buy this British government idea that the problems in the North are to do with religion – a religious divide and so on. There are very clear political, historical and economic reasons for what’s gone on in the North. It’s not down to two particular groups from a religious perspective having a difficulty with one another and the British government are the thin line in between or the meat in the sandwich. I don’t buy all of that.’

Storey was arrested a staggering 24 times before he was even 17. ‘I was absolutely in the thick of it. We engaged the British army on the streets. That was the shape of my Republican activism. I was very active and the British government had a determination to keep me off the street,’ he admitted.

Had he himself killed? ‘I certainly haven’t killed anyone... I’m not sure that there’s any role for ridiculous questions like that.’

During the Troubles there were several murder and kidnapping allegations made against him, but he was acquitted of them all. I said to him, ‘I’m thinking you were either very good or very lucky, or the authorities were very stupid?’

He replied, ‘It was swings and roundabouts. I would say – like many other Republicans – I was very active. The British government had a determination to keep me off the street. They used internment and when they weren’t able to use internment again they would fabricate evidence. They framed me. They actually pretended that I said things under interrogation which I never said. By the time of the hunger strike, I had done maybe seven years in jail with no convictions – all on remand. Internment by remand.’

If they were alleging that he’d done a dozen things, I responded, ‘I’m sure you must have been involved in some of them.’ In the book The IRA 1968-2000: Analysis Of The Irish Army, the author J Bowyer Bell wrote that ‘police had ample indication that Storey… killed on order, was a valuable IRA asset in Belfast...’

Bobby said, ‘Well, there’s been many things said about many people. All I can really say is that I was a Republican activist – like any other – and I was involved in all of that. It’s hard to quantify.’

Was he prepared to die for his beliefs? ‘I’d much prefer if people lived for the cause. On reflection, I wanted to do all that I could – and I still want to do all I can – to remove the British presence from my country. As a Republican activist, I took risks – does that mean I was prepared to die? It’s not a concept that I really thought about,’ he said.

‘I have been fired at, I have been beaten and, more recently, I have been threatened by so-called dissident Republicans. Of course, you’re fearful. There’s no doubt that I was in fear every day or worried – especially for family, friends and comrades. So, yes, you’re aware of the fear – but those aren’t aspects that would divert you in any way from your activism or ideological commitments.’

In 1979, he first hit the headlines when along with three others, he was arrested in a London flat after the authorities became aware of an elaborate plot to hijack a helicopter to free IRA boss Brian Keenan who was imprisoned at Brixton.

On that occasion, Storey was the only one acquitted. ‘My position in relation to that case is that I was innocent. I was a passerby. I went through a trial and I was acquitted of it. I’ll always remember being pinned to the bed by a police officer with a sawn-off shotgun and a flash lamp tied to it.’

Again, he was lucky not to receive a sentence for that. ‘You may describe me as a lucky man in that respect, but four months later I got 18 years for a gun battle with the British army. As I said, I suppose in many ways it’s swings and roundabouts in that regard,’ he replied.

‘We were arrested after there was a shooting incident with the IRA and the British army. There was a British soldier shot. And within minutes of him being shot, I was in a car with two comrades and we were rammed by an RUC divisional mobile support unit. We drove off and they fired after the car. We were chased through Andersonstown and we avoided being rammed by a British army vehicle and then we were cornered and arrested with two rifles.

‘We received 18 years for possession of the rifles. The type of sentences handed out for possession of weapons in those days, against Republicans, was far in excess to what was handed out to Loyalists. We were charged with shooting the soldier but we were acquitted of that. Our view was that even though we were only convicted for the rifles we were sentenced for the soldier.’

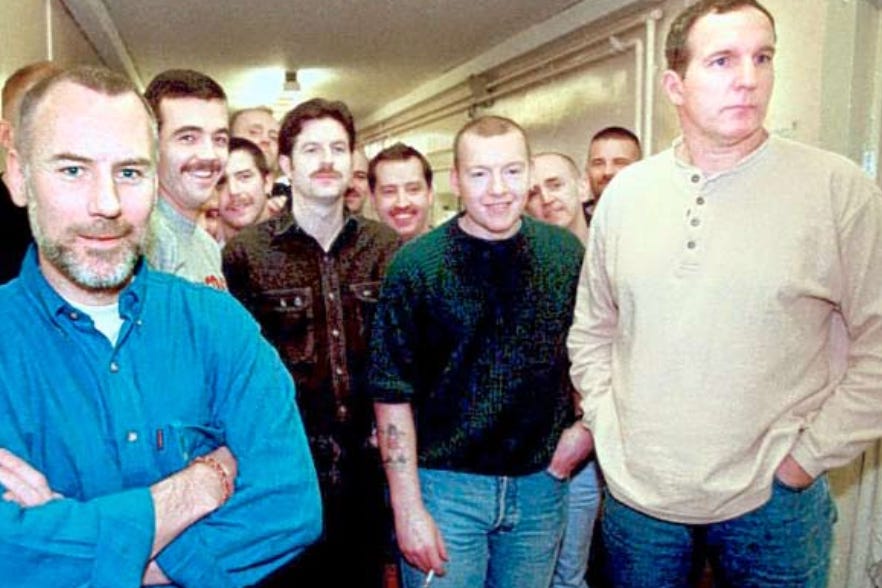

Storey then received further notoriety when he masterminded, along with senior Sinn Féin negotiator Gerry Kelly, the infamous Maze prison escape in 1983, which was the largest breakout of prisoners anywhere in Europe since the Second World War. But, unlike Kelly, who escaped to Holland, Storey was recaptured within an hour.

‘My biggest memory of the escape is that after I was captured and put in the punishment cell – after I was severely beaten – I was thinking, “We have done it”. We had busted the H-blocks and at the time they were being lauded as the most secure prison in Western Europe. We had struck a massive blow against Margaret Thatcher. And anything that damaged Margaret Thatcher would have been such a joy to me as a Republican,’ he told me.

Did a lot of planning go into it? ‘People who don’t know much about the escape might think of it as a wham bam, run, attack and climb over the wall, or ram the gate type of action. But – in actual fact – it was a very complicated operation,’ he stated.

‘We embarked on a deliberate strategy of relaxing the H-Blocks and relaxing the wings by having a more practical working relationship with the screws. That actually defused the tensions. It suited us because from a security point of view that gave us more psychological control and more territorial control within the wings and blocks.

‘It also created a less alert climate amongst staff because they weren’t fearful of us attacking them, and so they naturally relaxed. Some of them actually stopped carrying their batons and grills, which were normally locked, would be left open. It created the perfect conditions for us to carry out what then became the biggest escape in British penal history.’

Was he surprised that so many managed to escape? ‘The obstacles we had to face on the day were so substantial that I don’t think that any of us who had responsibility for the escape had thought about actually escaping to freedom. The obstacles were that great – we had to take over the block and manoeuvre through the jail, and we had to get the guns in previously. Many people had roles which involved them staying behind.’

On being one of the first to be recaptured, he said: ‘I was captured within an hour of the escape and I was brought to a punishment block and severally beaten, but I was absolutely enthused. My morale was sky-high. You could not annoy me – being captured could not undermine the euphoria I was feeling that day.

‘I was lying naked and battered and all I could think of doing was keeping my ear to the door to find out how many people were captured. I wanted to know, ‘Did we hammer them?’

‘For me, the most dominant thought that I had was that if the escape was a success it would absolutely devastate the British government. I wanted to ruin Margaret Thatcher’s life. I just wanted to get back at her. I wanted to shaft her. I wanted her hurt. I wanted her damaged. I wanted the British government damaged.’

He received an additional seven years on top of his sentence for his part in the Maze escape. But Storey was never in prison again after his release in 1998, following a two-year stint for allegedly having ‘information’ on then lord chief justice, Lord Hutton, and a British soldier.

What was the experience of prison like for him? ‘People on occasions talk about jail as very difficult and maybe the worst times of their lives, but I have no such memories... I couldn’t honestly say to you that the years I spent in jail were especially more difficult or better than the years I spent out of jail. And that’s the truth.’

During his incarceration, it was widely perceived, but never publicly confirmed, that he played an influential role in the peace process. Was that true?

‘Certainly, I have played a pivotal role in the peace process in general, as opposed specifically the Good Friday Agreement.’

It was also claimed that he was at the centre of meetings in South Armagh to encourage the hardline IRA there to stand down their weapons and obey the ceasefire. When asked about this, he carefully answered with: ‘I certainly have been part of meetings. I have been part of a series of discussions within Republicanism across the length and breadth of Ireland about Sinn Féin strategy and Republicanism in general and the direction of the party. I’ve spoken to all shades of Republicans the length and breadth of the country.’

In 2005, Ulster Unionist MP David Burnside told the British House of Commons – under Parliamentary privilege – that Bobby Storey was the head of intelligence for the IRA. ‘There have been many things said about me down the years – and I recognise that was one of them. But I have to tell you that I wasn’t the director of intelligence.’ He paused. ‘And then we had a laugh,’ he said, chuckling.

But there is no doubt in my mind that he was high up in the IRA ranks and on the Army Council. ‘I have never admitted to being in the IRA. I have never admitted to being in the Army Council. And I’m not on the Army Council. I have never been on the Army Council,’ he responed.

‘I’m a Republican activist. I’m very proud to be a Republican activist. I don’t have any interest in perceived authorities or titles. I have been a busy Republican activist all my life.’

Why was it that he wouldn’t – or couldn’t – admit to being a member of the IRA? ‘We don’t really talk about IRA membership – we talk about Republican activism. If someone said they were in the IRA, no matter how long they served in jail, they would be arrested, charged and sentenced. Very few people have been convicted of membership... I would also be barred from holding public office for the next five years; I could receive a sentence of up to ten years.’

On being described as the most successful Republican figure since Michael Collins, he said: ‘Well, I read that but I don’t really relate to it. The difficulty I have with assertions like that is that it ignores the amount of people involved in the likes of the escape or any operations. It’s always brought down to an individual character and personality which really isn’t reflective of the reality. Everything is a team effort. To look at history or events through an individual personality is not the way to appreciate the reality of the circumstances.’

Was he surprised when Freddie Scappaticci – codename Stakeknife – was discovered as being a mole? ‘An ever-present feature throughout hundreds of years of resistance, by the British ruling our country, has been the use of informants and agents to try and defeat our democratic objectives,’ he said.

‘So, it was hardly surprising that the British state throughout this latest phase of armed resistance adopted exactly the same strategy. So, was I surprised that the British state recruited informers to try and defeat the IRA?

‘No, of course I wasn’t. I’m a Republican – they were trying to defeat our struggle. Was I surprised that the revelations also revealed that the British state armed, controlled and directed the Loyalists’ gangs? Of course I wasn’t. It was Republicans who actually sought for years to expose it to a hostile and an uninterested media.’

He accepted that the IRA made ‘mistakes’ during their violent campaign. ‘Certainly, mistakes were made and people suffered,’ he said. ‘I empathise with anyone – Republican, Unionist, or otherwise – who as an innocent victim suffered through the struggle.’

Did he have any remorse for any of the Republican activities he was involved in? ‘There is a general emerging consensus and acceptance that Republicans of our generation were left with no other option. And, of course, it was those same Republicans who now create new options, created by the Peace Process. I think that debunks any notion that we threw ourselves into the oblivion of armed struggle willy-nilly. The most critical evolution since this struggle began was achieved by those most active and engaged with in it,’ he said.

‘We Republicans have our own code of human ethics and measure our involvement and actions against that. And for my own part, I have not brought myself or the struggle I represent into disrepute. Had we Republicans not conducted ourselves with honour, our own community would not have supported us in the way that they did. I generally don’t have a particular remorse about any particular thing.

‘Armed struggle and war is very difficult. There is no monopoly on suffering. There’s no monopoly on mistakes. I regard myself as a very honourable, proud Republican activist. I would say there are many regrets by many people, including myself, on a specific matter, but in very broad terms I am quite satisfied by the direction my political life took.’

Rather than dwelling on details of the North’s violent past, he insisted that everyone must look to bringing about a peaceful future for this island For his part, he wanted to persuade these dissidents to end the violence.

But wasn’t the Good Friday agreement a compromise? ‘No, for me it isn’t categorised as a compromise. Everybody who signed up to the Good Friday Agreement obviously had an analysis that it served their particular politics better. When we signed up to the Good Friday Agreement it was because we thought that it served the Republican agenda more than it served anybody else. No doubt everybody signed up to it on that basis,’ he said.

‘But who was right and who was wrong? Now, ten years later, Republicanism is stronger on the island of Ireland than it was at any other time in the past. There are more Republicans on the island of Ireland. There is more [Sinn Féin] representation on the island of Ireland now than there was at any other time in the past. Where is the SDLP? Where is the UUP? Before the Good Friday Agreement was signed, we had 90,000 votes across the island of Ireland in a European election – and today we have a third of a million votes.’

Ian Paisley Jnr. told me once: “Republicans wanted to get rid of the British from Ireland – that was their project. They did fail.” So, were the IRA defeated?

‘Absolutely not. The IRA were never defeated. The IRA did not defeat the British government and certainly the British government did not defeat the IRA or Republicanism,’ he concluded.

‘Ian Paisley Jnr. also said – along with his father – that they were going to smash Sinn Féin and going to destroy Republicanism – and that Republicans would not be in government! Actually, we have dragged Unionism millimetre by millimetre across lines that they said they would never cross. Ian Paisley was in government with Martin McGuinness. The DUP are in government with Republicans – with ex-prisoners. We have brought them to that point.’

© Jason O’Toole 2024